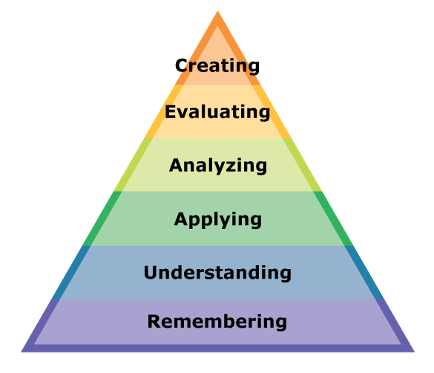

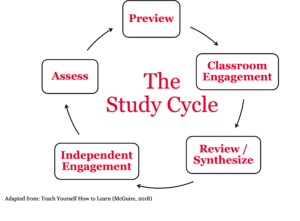

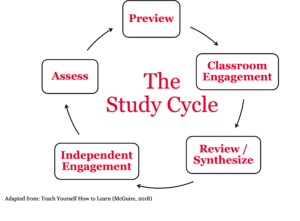

Now that you are aware of the hierarchy of learning levels presented in the Bloom’s Taxonomy pyramid, it is important to develop effective (and efficient) study strategies so you are an engaged learner (traversing the different levels of the pyramid) that retains the information for future recall. Each time you engage with new material – via class sessions, readings, videos, or other mediums in which you receive information – your neural networks expand. When these neural networks are frequently activated/visited – such as when you study materials or practice skills – these new networks have the potential to become long-term memories. Repetitive activation of these networks strengthens connections and recall of this information (for a test or exam for instance) is increasingly easier. Here we will discuss the 5 stages of the Study Cycle – a cyclical approach to your learning that will enhance your engagement with the course material and promote deeper learning.

To begin, you must Preview the content ahead of time. This preview step does not have to be a huge time commitment. Within the reading you can flip/scroll throughout the pages and notice terms, concepts, headings, etc. If the instructor posts materials before class (i.e., Powerpoint slides), then look through the slides and familiarize yourself with what topics or concepts are going to be addressed in that class session. Generate your own questions concerning what you believe you would be able to answer by the end of the reading and/or class attendance. If you are in a class where you are assigned practice problems/homework, you should peruse the practice problems/homework prior to attending class. If you are in a class where there is no textbook, then what other material may be provided by the instructor? At a minimum you can look over the material from the previous class session to refresh your knowledge about what was covered and why that important to the overall course. This Preview step can be as short as 10-15 minutes, where you are priming your brain for what you will address in the subsequent class session.

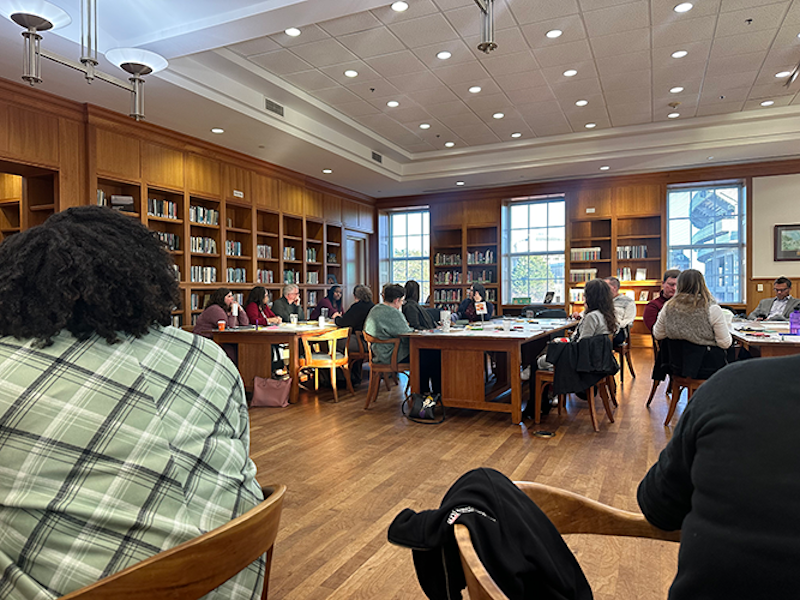

This brings us to the second step in the Study Cycle – Classroom Engagement. It has to be more than just attending class. Just sitting there is not going to be as productive and useful as you may hope. You need to be engaged in the learning experience. Think about where you sit, who you sit next to, do you come prepared for class, are you on time for class, do you have a set of questions you are ready to have answered on that respective subject you will cover in that class session? All of these questions (and likely many, many more) should come to mind as you evaluate how you are an engaged learner in each and every class session. For large “lecture” style classes, you can still be engaged and an active participant in the learning experience. For medium and smaller classes, it may be harder to fade into the “background” of the class. Whatever the class size, type, or structure you can be engaged in the learning process. Some instructors may be very clear about classroom engagement practices, and others may not be. So think about how much you want (and need) to get out of each and every class session so you maximum what you gain in that learning environment.

The third step of the cycle is Review / Synthesize. Here you are encouraged to look back over your notes or course materials after that class session and recognize what was covered and why was it covered. This “what and why” approach to evaluating that classroom experience will let you see what material or concepts you feel comfortable with and what material you are going to need to dedicate extra attention. In this Review/Synthesize step you can take inventory about how much time was dedicated to a particular topic from that class session. If an instructor spent a large portion of a 50 minute class covering one specific topic, then that should prompt you to recognize the importance placed on that material. This step of the Study Cycle also allows you to evaluate those initial questions you had on this subject during the Preview step, and see if clarification was provided from the class session. If your questions were answered, then great! You now see what you have gained in your learning. If some or all of those Preview questions still remain, then you now have some direction in your studies to find the answer – from the course materials, by attending the instructor’s office hours, speaking with a Teaching Assistant, speaking with a study partner or tutor, etc. And like the Preview step, this Review/Synthesize steps does not need to be overly time consuming. This step is actually helping set the stage for the next step in the Study Cycle.

The forth step of the Study Cycle is Independent Engagement. Independent Engagement consists of the academic work you do outside of class – studying, reading, writing, homework, etc. This independent engagement is done on your own time; time that you have now identified from completing the Time Management module (Module 2). If you have worked through the first 3 steps of the Study Cycle, then by the time you get to Independent Engagement you should have a very clear idea of what you need to work on and how you plan to tackle that work. This Independent Engagement step of the Study Cycle can be subdivided into four key steps: Set a Goal, Do the Work, Take a Break, and Return to Review.

- Set a Goal – Setting a goal for each Independent Engagement session will be necessary to staying on track and on target for the work you are wanting/needing to accomplish. This goal (or goals) will be based on the insight you have gained from Previewing, Classroom Engagement, and Review/Synthesizing that material. You now know what you need to learn on a deeper level. Setting a goal will allow you to have something you are working towards, under a defined amount of time.

- Do the Work – Here is where the “rubber meets the road” so to speak. You now have to put in the time to your academics outside of class, but you have some direction of what you are working on and how you plan to accomplish it with the goal(s) you set. The “Do the Work” step must have a time constant though. You cannot think that you will be super productive sitting in the library for 8 hours of non-stop studying. Scale it back to a very defined target of what you want to accomplish and be sure to stay on task for the duration of the work. If you know that your phone is a big distraction, then turn it to Do Not Disturb and put it out of sight. This may be a struggle for self-control and will power. And what will help in not feeling temped to be on your phone is what is coming in the next step – your break. The duration of work you do during the Do the Work step should be contingent on what the goal(s) you set at the onset. If the goal is very narrowly defined, then 25 – 30 minutes may be sufficient. If your goal is a little more ambitious, then maybe 45 – 60 minutes is more appropriate. But be sure to not go beyond 60 minutes of continuous studying, before you get to your break.

- Take a Break – Yes, you read that correctly. Have a planned break in your work schedule so that you do no burn out or become to mental drained/exhausted. This planned break is to be just that, a break for your brain to rest and absorb what you just worked on. Don’t take a break from one class to just work on another class. This break could consist of a restroom break, water/food break, and/or technology break. You have probably been wanting to see what you have been missing on your phone, so take some time to get caught up there. Keep in mind though, the duration of this break is dependent on the duration of your work session. If worked diligently for 30 minutes, then take a 5 minute break. If you worked for 60 minutes, then take a 10-15 minute break. But be sure to stick to these time limits, its important to not get too off task here.

- Return to Review – This is where you will come back to your studies, writing, reading, or homework and take some time to look over what you just accomplished. It may be tempting to pick up right where you left off and continue working, but please take some time to evaluate what work you had done and take inventory if you feel you have truly accomplished the goal(s) you set out to do. If looking over your goal(s) and then the work you have done you may realize that you achieved your goal(s). Wonderful! Now you know what you have learned and are ready to take on the next set of goals in subsequent Independent Engagement sessions. You may find out in this review that you did not achieve the goal(s) you established at the start. That is also ok, since by taking this review time to see what area you need to dedicate additional attention to so that you master that subject before you move on to the next topic.

If you follow these 4 steps to the Independent Engagement work, you will begin to recognize how much learning you are doing. The maximum time of a full Independent Engagement session will be about an hour and a half. But you know that you need to put in more time than that to stay on top of your work. So, the recommendation is two or three Independent Engagement sessions back-to-back before you take a much longer break. These longer breaks may be for a meal, exercise, some social time, or even “me time”. And remember what was discussed in Module 2 – the target of the 8-8-8 rule is 8 hours of Academic Work a day for a full-time student. That means, if you are in class for a total of 3 hours one day, then you have 5 hours of Independent Engagement you will need to do. So, identify when in your daily schedule you will get that work done.

The final step of the Study Cycle is Assess. In this Assess step you need to test your knowledge on all of the material you have covered for the last several days or week. Assessing your knowledge will allow you to see what information you have retained and what needs to be revisited for ease of recall. Potentially for some students, this Assess step is where you begin to introduce time as a factor in your study approach – meaning you set a time limit to how long you take to complete a practice exam question. You may have spent as much time as you need to work on the homework or problem sets for a class, but now you need to incorporate the time constraint that you will have on the assessment. If it is taking you 30 – 40 minutes to solve a homework problem, and you only get on average 6 – 8 minutes per question on an exam, then what steps are you taking to incorporate time into your preparation strategies for that assessment? Assessing your knowledge will allow you to be confident in your knowledge base on that respective topic/subject, before you move onto the next subject and add more to your expected learned material.