Reading efficiency may not be the first area that comes to mind when you think about academic strategies propelling you into success, but this skillset can also help you improve time management and general study skills! Experts agree that adopting an active reading mindset is key to maximize your understanding of texts. Key research-proven strategies include a quick pre-reading activity, annotating, outlining/ diagramming, analyzing, identifying patterns, and more. To best utilize this section, start with the Strategies section to familiarize yourself with the evidence-based strategies to effective and efficent reading. Next, peruse the Read Further section for more support in mastering this skillset. Finally, put your new skills into practice with the help of the featured apps. For feedback on your strategy implementation and to revolutionize how you read for understanding, schedule an appointment with one of our academic coaches!

Strategies

The Importance of Reading Efficiency

Being able to read well is fundamental for your success in college, and it can save you time! In most courses, you are expected to read, understand, and recall information from the readings. However, some of you may remember a time when you would spend hours doing the readings but not being able to take in much information or being able to remember what you read. This is often because you view reading as a passive activity.

To improve your ability to understand and recall what you read, you will be need to be more actively engaged and strategic in this process. The following are strategies that you can use to become a more effective and efficient reader.

Identifying Your Goals

Your professors assign the readings for a reason, to help you learn the content. Before you start reading, try to identify which specific content you are supposed to learn from the texts. A course outline is a good place to find out about the content that will be covered through a particular set of readings.

Taking Stock of What you Already Know About the Topic

For the most part, you are not a blank slate. Simply taking a moment to think about what you already know about the topic can help you connect your prior knowledge with the new information that you are about to take it in. It will help you understand and remember the new information much better.

Previewing

Two experts (Bransford & Johnson, 1972) asked college students to read the following paragraph. Try reading it for yourself and see how much you can understand and remember.

A newspaper is better than a magazine, and on a seashore is a better place than a street. At first, it is better to run than walk. Also, you may have to try several times. It takes some skill but it’s easy to learn. Even young children can enjoy it. Once successful, complications are minimal. Birds seldom get too close. One needs lots of room. Rain soaks in very fast. Too many people doing the same thing can also cause problems. If there are no complications, it can be very peaceful. A rock will serve as an anchor. If things break loose from it, however, you will not get a second chance.

You probably recognized all the words in the paragraph, yet you might have a hard time figuring out what the passage was about. The good news is that you are not alone. Most people don’t remember what they have read after reading this paragraph for the first time. Let’s try this again, but this time, keep in mind the title “Flying a Kite”. You should be able to make much better sense of the passage when it is put in a meaningful context.

This exercise is meant to show you the importance of previewing the text before you start reading.

Previewing is when you skim through the entire text (e.g., a chapter or an article) to get an overview of what you are about to read.

- Pay attention to the title and different sections of the text to give yourself a roadmap (i.e., how the text is organized).

- Quickly skim the first (or the first few paragraphs if the text is rather long) and ask yourself what you expect to learn from the text.

- Quickly skim the last paragraph (or the last few) which often summarizes the main points discussed in the text.

- See if there are any comprehension and discussion questions. Read these questions before you start reading the text to help you focus on important information while you read.

- Then spend a few minutes writing down what you have learned from the previewing process. You might not get everything right since you have not actually read the text yet; however, your initial notes will help you make sense of the text as well as reshape the goals of doing the readings you set initially.

Active Reading

To make the most out of the time you spend doing the readings, you will need to turn off cruise-control and start steering! In other words, you will need to take a more active role when reading. Here are some strategies skillful readers use.

- Think of reading as having a conversation between the author and yourself. Ask yourself this question: “what is the author trying to tell me here?”

- Try to identify the main ideas in the text.

- Sometimes main ideas are easy to spot as they are directly stated at the beginning or the concluding part of the paragraphs.

- Other times, they can be inferred from facts, reasons, or examples.

- If the text has headings, turn them into questions and answer them. Broadly speaking, there are two levels of questions. Lower level questions require you to remember and understand what you read, while higher level questions encourage you to apply, analyze, synthesize and evaluate Once you’ve turned the headings into a question, you can underline or highlight relevant parts of the text that answer your questions. Creating and answering both lower and higher level questions from the headings can help you prepare for all types of exam questions. Because you are actively engaged with what you read, this makes the information more meaningful to you and helps you retain it much better. See examples of different levels of questions created from the text headings here*.

- Try to identify the main ideas in the text.

*Source: https://mtsac.instructure.com/courses/56468/assignments/179126

- Annotate what you read. Annotation (or writing in the margins) is another way to have a conversation with the author. In addition to identifying the main points, or “what is the author trying to tell me here?”, you can record your ideas as they come to you while you are reading. These thoughts can be your honest personal reactions to the text, connections between your previous experiences and the readings, connections between what you are reading now and what you have read in the past (in this course, or other courses you have taken or are taking). You can also ask questions about the content of the text. You can ask these questions in class or during your professor’s office hours. This is particularly helpful if you are trying to find ways to participate in class discussion. Another way to annotate the text is to identify new words. You might not need to know the meaning of these new words right away to understand the readings. However, it is probably a good idea to look up the definitions of some words, especially ones that you come across several times in several readings.

- Monitor your comprehension. Ask yourself whether you are taking in or understanding the information you are reading. If not, try to figure out why you are not understanding the text. Here are some common reasons for reading comprehension problems and what you can do to overcome them.

- If the text contains unfamiliar words, try using the context to figure out the meanings. If the context is not helpful, use a glossary (if available) or a dictionary.

- If you have a hard time concentrating, identify the distracters (e.g., your roommate, physical environment, hunger, etc.) and remove them or yourself from the distracting environment.

- If you have very little background on the topic you are reading, try to learn about the topic from reputable sources such as Encyclopedia Britannica or Oxford Bibliographies. Then reread the text again.

Reviewing What You Have Read

To make sure that you actually understand what you read and will be able to recall the information later, you will need to get the information into your long-term memory as soon as possible. To help you make better sense of the information that you have read and organize it in ways that enable you to retain it in your long-term memory, you can try using these strategies.

- Test yourself on the questions you have created based on the headings. If you cannot answer these questions, you do not understand the content.

- Try summarizing what you have read. See if you can include the following information in the summary:

- The main points

- Key supporting points

- Definitions of key terms, concepts or theories

- Try creating an outline of the readings. For complex material, an outline can show relationship between different levels of ideas (e.g., main points and supporting details).

- Try creating visual representations of what you have read.

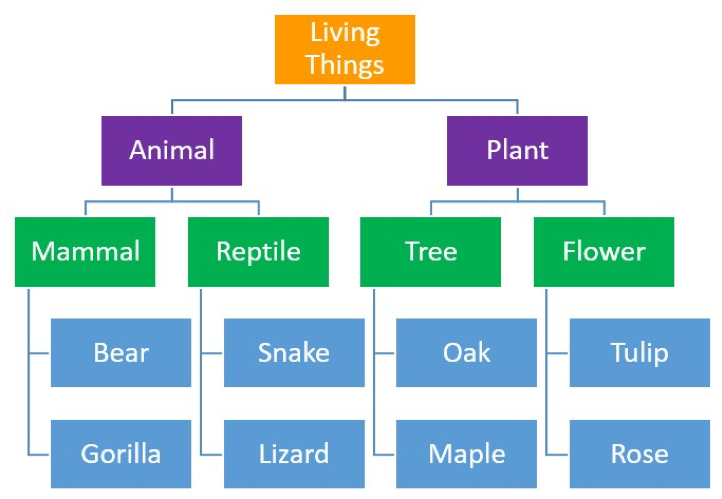

- Hierarchies – Ideas can be organized into levels and groups, with higher levels being more general than lower levels as illustrated below.

Image source: http://thepeakperformancecenter.com/educational-learning/learning/memory/stages-of-memory/organization-long-term-memory/

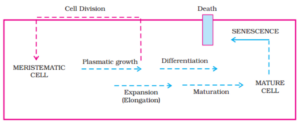

- Sequences – Ideas can be organized chronologically to show order of steps, events, stages and phases. The example below illustrates stages of plant development.

Image source: https://www.askiitians.com/biology/plant-growth-and-development/

Sequence of events in history can also be illustrated.

Image source: Encyclopedia Britannica

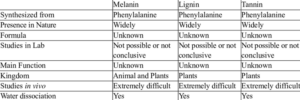

- Matrices – A matrix can be used to show comparative relations of the content. Comparative relations are represented through the three components of a matrix – topics, repeatable categories and details inside the matrix cells. The topics are located across the matrix (e.g., Melanin, Lignin, and Tannin). These topics are often identified in the text by the author. The categories of characteristics by which the topics are compared are listed on the left-most part of the matrix. You may need to identify these categories based on the information the author provided. The matrix below illustrates the structure-properties-function relationship of Melanin, Lignin and Tannin.

The structure-properties-function relationship of Melanin, Lignin, and Tannin

- Diagrams & Concept Maps – Diagrams can be used to show components of objects or concepts. For example, a diagram can help you memorize different parts of the brain in a Biology class, or different countries in a particular geographic region in a geography class.

Image source: http://www.brainwaves.com/

- Concept maps can be used to show different components of a topic and the relationship or connection among the different parts. For example, it can be used to help you understand the concept of electric charge.

Image source: https://physicscatalyst.com/Class10/charge_concept_map_class10.php

Further Reading

Links for Improving Reading Comprehension

- This checklist highlights 6 key reading habits for active reading, complete with specific suggestions and explanations of how to implement these critical strategies.

(Interrogating Texts: Six Reading Habits to Develop in Your First Year, by Harvard Library; https://guides.library.harvard.edu/ld.php?content_id=44324954)

- This article explains why and how to annotate your readings. Beyond names and descriptions of successful strategies, you’ll find a useful sample of a model annotated reading.

(The Writing Process: Annotating a Text, by Rockowitz Writing Center, Hunter College, City University of New York; http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/rwc/repository/files/the-writing-process/invention/annotating-a-text.pdf (PDF))

- This concise menu of options of active reading strategies is an approachable summary keep next to you as a reminder while you read.

(Active Reading Strategies: Remember and Analyze What You Read, by The McGraw Center for Teaching & Learning https://mcgraw.princeton.edu/active-reading-strategies

Recommended Apps

Dictionary.com

Access to essential and most comprehensive dictionary app for dependable definitions at your fingertips.

Notability

Combine handwriting, photos and typing in a single note to bring your projects to life. Note: This app is only for iOS and requires a one-time purchase of $9.99.

SimpleMind Lite

Mind mapping helps you organize your thoughts, remember things and generate new ideas. This app can help you mind map concepts covered in your classes and in your reading, to better understand the complex material covered.